[Twenty] First Century Pedagogy?

There’s an image of ‘traditional’ teaching as filling students up with knowledge, rote learning, absent of any context or interest. Every other day someone dutifully reposts the latest diatribe on social media, exhorting teachers to embrace 21st century values and reject all that old-fashioned, straightjacketed learning.

I wonder where, exactly, these people went to school. Were they lined up in rows, dutifully reciting times tables all week?

I recall times tables and spelling. But I also recall sitting in groups around tables creating projects, and pushing those tables aside and putting on Shakespeare plays, having swordfights with metre rulers. You want PBL? My year 10 class built an actual bridge, because we needed one. And this was an ordinary state school.

I recently returned to my study of Greek. Could there be a more archaic and staid model of education than that around the learning of a classical language? You’d think not, but then I opened Homeric Greek, A Book for Beginners, and read the advice from Clyde Pharr ‘To Inexperienced Teachers’. In this short preface you’ll find principles that most of us would like to think of as cutting edge; but this book was first published in 1959, the very year that Dead Poet’s Society was set, with its model of the soul lost to rigid tradition, the teacher of classics, Mr McAllister, quietly intoning ‘agricola, agrolae, agricolarum…’ as he gazes absently out the window.

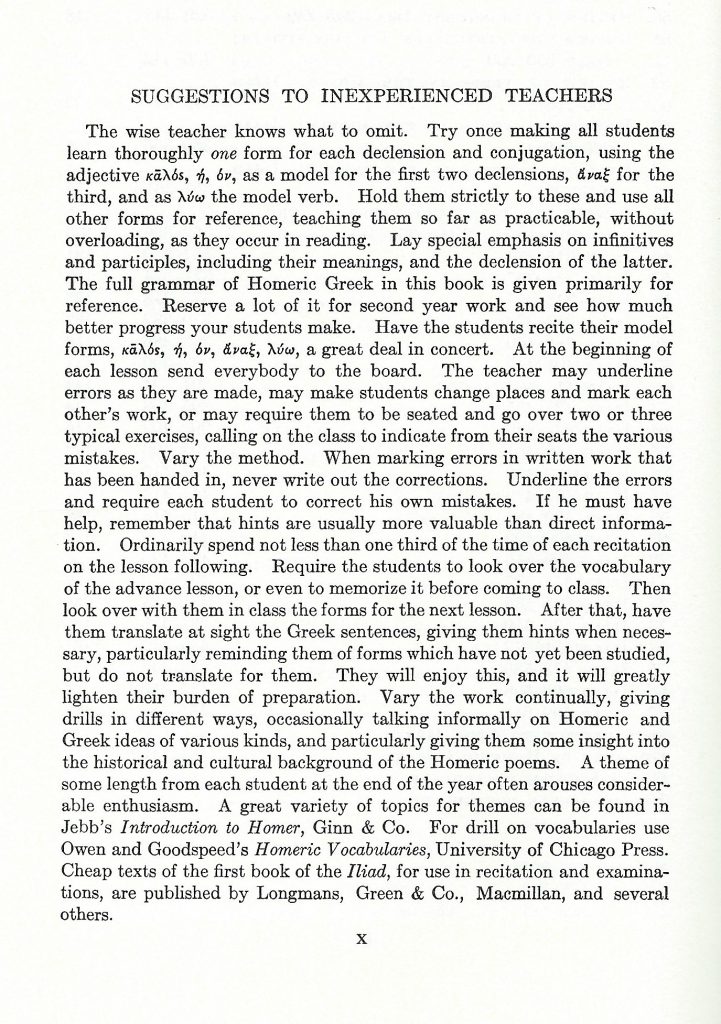

Sure, there’s rote learning; but Pharr exhorts the teacher to focus on some key forms, and reserve much until the student has found their feet. The advice that follows wouldn’t be out of place in any contemporary teaching manual:

At the beginning of each lesson send everybody to the board. The teacher may underline errors as they are made, may make students change places and mark each other’s work, or may require them to be seated and go over two or three typical exercises, calling on the class to indicate from their seats the various mistakes. (Collaborative, peer-to-peer learning:)

When marking errors in written work that has been handed in, never write out the corrections. Underline the errors and require each student to correct his own mistakes. If he must have help, remember that hints are usually more valuable than direct information. (Scaffolded self-correction:)

Require the students to look over the vocabulary of the advance lesson, or even to memorize it before coming to class. Then look over with them in class the forms for the next lesson. (Flipped Classroom:)

After that, have them translate at sight the Greek sentences, giving them hints when necessary, particularly reminding them of forms which have not yet been studied, but do not translate for them. (Situated learning)

Vary the work continually, giving drills in different ways, occasionally talking informally on Homeric and Greek ideas of various kinds, and particularly giving them some insight into the historical and cultural background of the Homeric poems. (Learner-centered practice:)

I’m not advocating for a return to Classical education, but rather for a willingness to recognize the value in the work that has gone before, both in what we carelessly reject, and in what we fail to acknowledge with our claims of innovation.

I should add (thank you for the reminder, Dr. Howitt) that rote learning is, nonetheless, important. I often argue that, contrary to current dogma, it’s not enough to teach ‘how to think’; one needs something to think with. Information – facts, figures, dates – and in this case, nouns and verbs – are what you think with. You can’t build a fire without fuel – all your hot air will go to waste if you don’t feed it with something solid. Working with material in context is always valuable, but for some material, rote learning still has a place.

To be honest, I’m quite fond of Mr McAllister’s gentle recitation.